Reading And Recovering Data From FATX File Systems

This is a write up for the data recovery tools I created for the Xbox and the Xbox 360. My goal is try and give users a greater understanding into how these tools work so that they may possibly be improved upon or just as an aid for doing manual data recovery. I will cover the FATX file system and methods for data recovery. There are currently two open source repositories on my GitHub for fatx-tools.

Python: fatx-tools

C#: FATX-Tools

Introduction to FATX

The original Xbox and the Xbox 360 uses a file system named FATX, which is a variant of the FAT file system, created specifically for these two game consoles. It supports both 16 and 32 bit file allocation tables, which will depend on the size of the partition. A harddrive will contain multiple partitions, some of which contain FATX file systems, and others that don’t. We will only be focusing on the partitions that do contain FATX file systems as it is these that contain game and user data.

Partition Layout

You can use this documentation to navigate your way to a particular partition. The most interesting partition in my opinion is Partition1, which contains game and user data. There are other partitions that use the FATX file system but these usually have nothing other than system or cached data. Once you have navigated your way to the desired partition, the next sections will be working on offsets relative to that partition into the FATX file system.

Xbox Partitions

The original Xbox uses static partition offsets and lengths.

| Offset (in bytes) | Size (in bytes) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0x80000 | 0x2ee00000 | Partition5: Cache |

| 0x2ee80000 | 0x2ee00000 | Partition4: Cache |

| 0x5dc80000 | 0x2ee00000 | Partition3: Cache |

| 0x8ca80000 | 0x1f400000 | Partition2: Stores dashboard data |

| 0xabe80000 | 0x1312D6000 | Partition1: Stores game and user data |

Xbox 360 Partitions

The partition layout is different for both retail and development kits. Partition layouts are documented in the link below. Note that the offsets and lengths are documented in sectors, so you need to multiply the values by 0x200 to get to the true offset. They have changed since earlier kernels, so be sure to verify that the partition layout matches yours.

Retail

Retail systems, like the original xbox, have static offsets for each partition. Partition1 has its length determined by the size of the harddrive.

Development

Development kits have a partition table at the very beginning of the hard drive with the following structure:

| Offset | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0x0 | u16[4] | Kernel version |

| 0x8 | u32[2] | Partition1 offset and length in sectors |

| 0x10 | u32[2] | SystemPartition offset and length in sectors |

| 0x18 | u32[2] | Unknown |

| 0x20 | u32[2] | DumpPartition offset and length in sectors |

| 0x28 | u32[2] | PixDump offset and length in sectors |

| 0x30 | u32[2] | Unknown |

| 0x38 | u32[2] | Unknown |

| 0x40 | u32[2] | AltFlash offset and length in sectors |

| 0x48 | u32[2] | Cache0 offset and length in sectors |

| 0x50 | u32[2] | Cache1 offset and length in sectors |

FATX Structure

Header

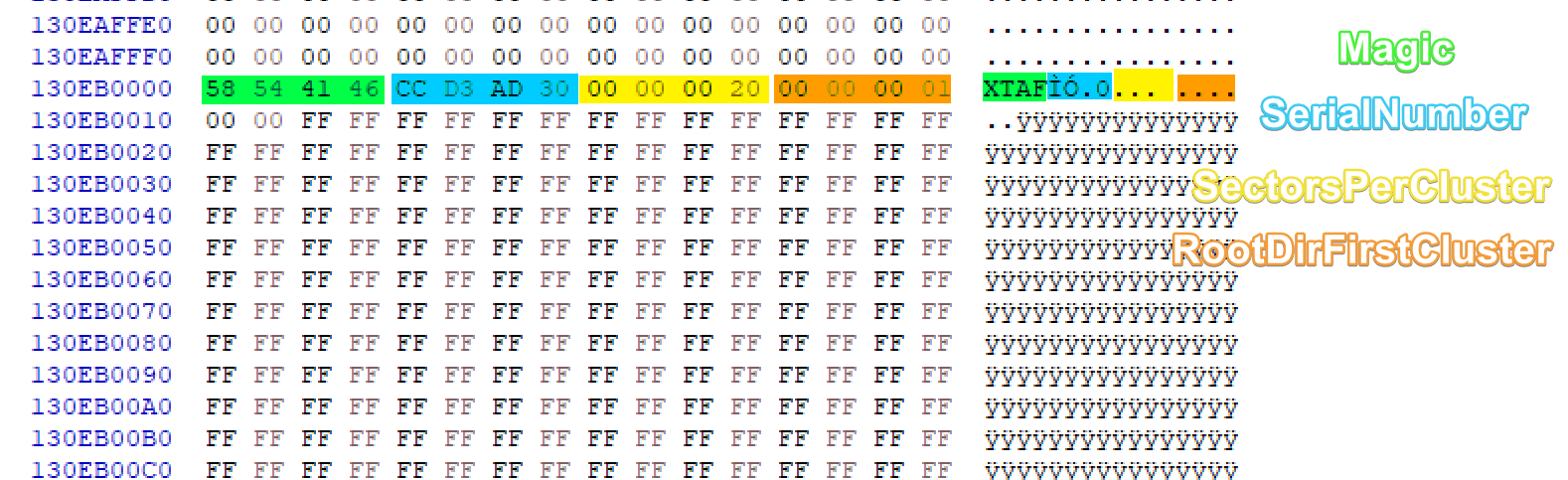

The file system starts off with a pretty simple FATX header at the very beginning of the partition.

| Offset | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0x0 | u32 | Magic should be equal to “XTAF” (Yes, “XTAF” not “FATX”). Note that on little-endian systems (Original Xbox), you will see “FATX” only due to the endian swap. |

| 0x4 | u32 | SerialNumber is not important but it is initialized to be the system time at the time of format using KeQuerySystemTime(). |

| 0x8 | u32 | SectorsPerCluster This can technically be accepted as any power of two, less than 128 (2^n = 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128), but for FATX, this seems to always be initalized to 0x20. |

| 0xC | u32 | RootDirFirstCluster This is the index of the cluster where the root directory exists and appears to always be set to 1. |

| 0x10 | u8[0xFF0] | Should be unicode Volume Name in here but it doesn’t ever appear to be used so we will ignore this. |

According to the header we can calculate the cluster size that will be needed to read the file system. The sector size is always a constant 0x200 bytes therefore the cluster size can be calculated as the value in SectorsPerCluster in the header multiplied by the sector size. We will use 0x20 as SectorsPerCluster because it seems that is always what it is initialized as, therefore the cluster size is 0x4000.

The total size of the FATX header is 0x1000 bytes. Immediately after this header is the file allocation table (FAT).

SectorSize = 0x200

// Amount of bytes in a single cluster

BytesPerCluster = SectorsPerCluster * SectorSize = 0x4000

// Offset of the file allocation table

FatByteOffset = 0x1000

File Allocation Table

The size of the partition determines the type of this FAT. If the partition contains less than 0xFFF0 clusters, then this FAT will have 16-bit entries, whereas if it contains greater than 0xFFF0 clusters, then it will have 32-bit entries. The number of entries in the FAT (also MaxClusters) is equal to the partition length divided by BytesPerCluster, then add 1 for the reserved cluster. The FAT contains an entry for every cluster and the length of the FAT is aligned to the nearest page (0x1000 bytes). Here we will calculate 2 values needed to read the file system.

PageSize = 0x1000

// Number of entries in the FAT

MaxClusters = (PartitionLength / BytesPerCluster) + 1

// FAT total size

BytesPerFAT = ((((IsFatX16) ? 2 : 4) * MaxClusters) + (PageSize - 1)) & ~(PageSize - 1)

Entries in the file allocation table will be set to zero if the cluster is available. If the cluster is not available, then it will be set to the next cluster index in the cluster chain or one of the following constants:

ClusterReserved = -16 // 0xfffffff0 or 0xfff0

ClusterBad = -9 // 0xfffffff7 or 0xfff7

ClusterMedia = -8 // 0xfffffff8 or 0xfff8

ClusterLast = -1 // 0xffffffff or 0xffff

See File System Operations for more about how the file allocation table is used.

File Area

The file area is referred to as the area after the file allocation table. This area is where file data and directory entries are stored and continues on until the end of the partition. To get here, we add the size of the FATX header (0x1000) and the size of the FAT.

FileAreaOffset = BytesPerFat + FatByteOffset

The file area is also where clusters begin. An important note to make is that clusters in the file area begin at cluster index 1 rather than 0 because the 0th cluster is reserved. Navigating to a specific cluster in the file area needs to be done like so:

OffsetByCluster = FileAreaOffset + ((Cluster - 1) * BytesPerCluster)

Directory Entries

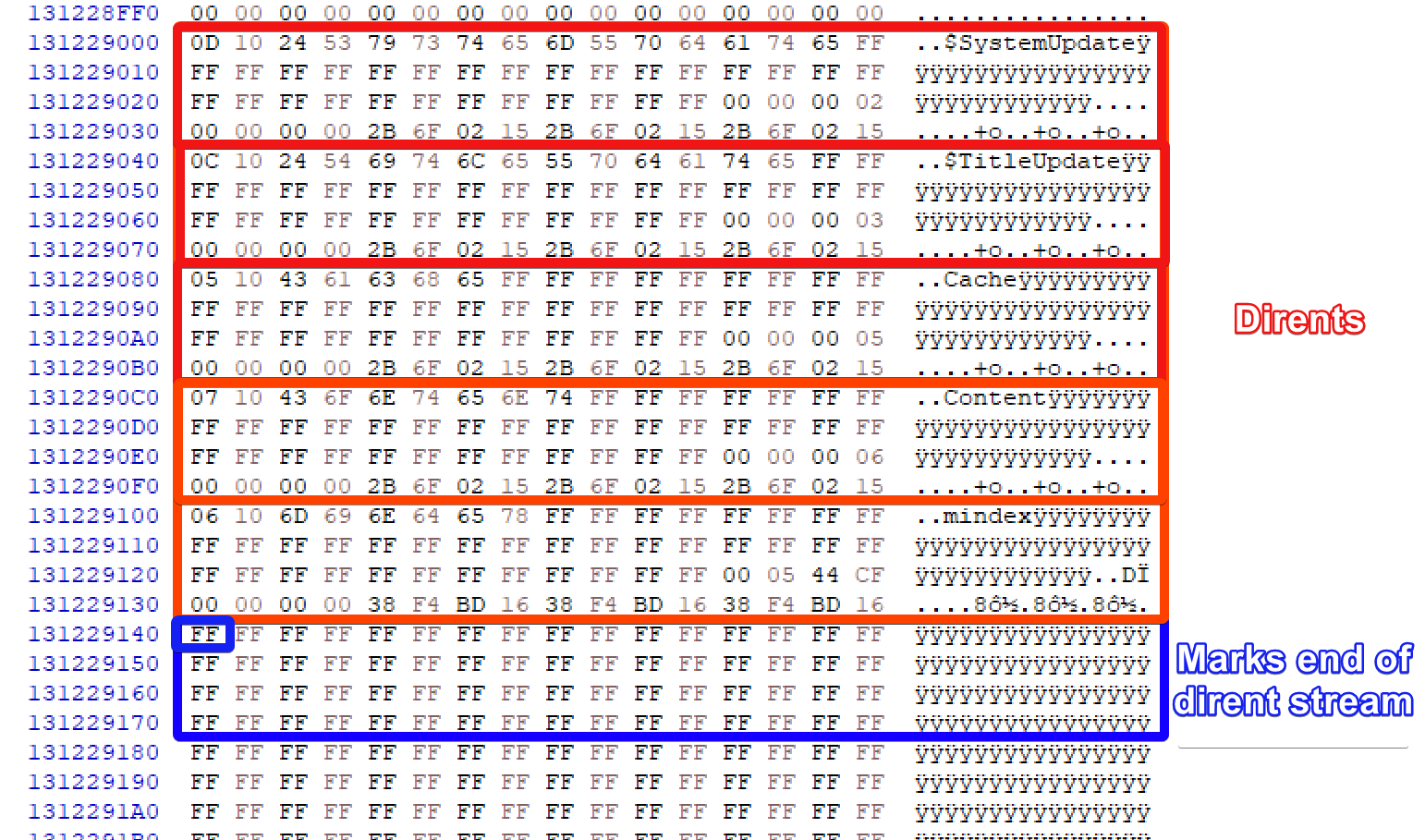

A directory entry represents one file or directory and contains information about it. We will refer to a directory entry as a dirent. One dirent takes up 0x40 bytes as seen in the image above and the structure below.

An entire cluster is reserved for a “stream” of dirents. Thus, as we know a cluster is 0x4000 bytes, each stream contains 0x100 (256) dirents. Each stream makes up some or all contents of a single directory. Normally, we would read dirents consecutively within a stream until we run into one which has the FileNameLength set to DIRENT_NEVER_USED2. This would mark the end of a directory.

The root directory starts at the cluster whose index matches that of RootDirFirstCluster from the FATX header. From there we can begin reading the dirent stream that makes up the root directory.

| Offset | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0x0 | u8 | FileNameLength is either set to one of the constants below or the amount of characters that make up the file name.DIRENT_NEVER_USED = 0x00 DIRENT_NEVER_USED2 = 0xFF DIRENT_DELETED = 0xE5 |

| 0x1 | u8 | FileAttributes contains bit flags for this file. If FILE_ATTRIBUTE_DIRECTORY flag is set, then this is a directory, otherwise it is a file.FILE_ATTRIBUTE_READONLY = 0x01 FILE_ATTRIBUTE_HIDDEN = 0x02 FILE_ATTRIBUTE_SYSTEM = 0x04 FILE_ATTRIBUTE_DIRECTORY = 0x10 FILE_ATTRIBUTE_ARCHIVE = 0x20 |

| 0x2 | char[42] | FileName is the file name. File name cannot be 0 length and cannot be “.” or “..”. Valid characters:

|

| 0x2C | u32 | FirstCluster identifies the first cluster which contains either the file’s data, or the directory’s dirent streams. |

| 0x30 | u32 | FileSize is the file’s size. This would be set to 0 for directories. |

| 0x34 | u32 | CreationTime is the timestamp for when the file or directory was created. |

| 0x38 | u32 | LastWriteTime is the timestamp for when the file or directory was last written to. |

| 0x3C | u32 | LastAccessTime is the timestamp for when the file was last accessed, or read from. |

Timestamps use the following bit-field format packed into 32 bits:

| Bit-range | Description |

|---|---|

| 0-6 | Year |

| 7-10 | Month |

| 11-15 | Day |

| 16-20 | Hour |

| 21-26 | Minute |

| 27-31 | DoubleSeconds |

File System Operations

Reading Contents of a Dirent

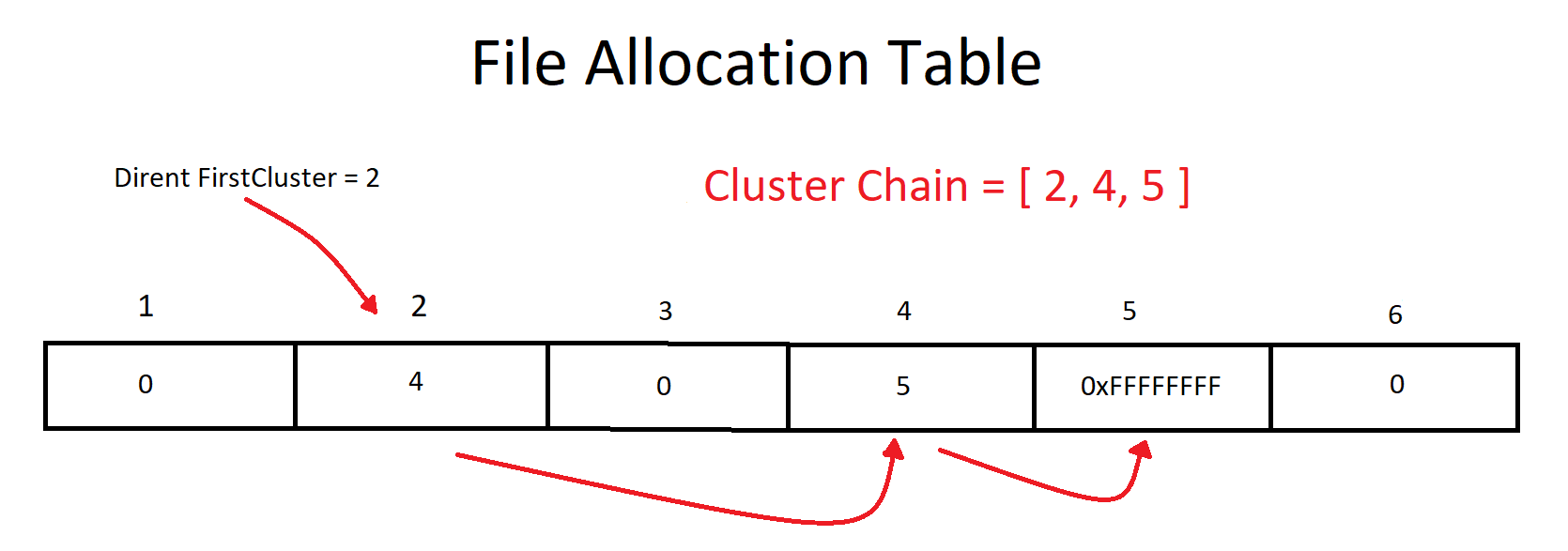

In order to read the contents of a dirent, we begin with the dirent’s FirstCluster as the first index. We extract the value at that index from the file allocation table, and that extracted value will give us the next cluster. This is done until the extracted value is equal to ClusterLast which marks the last cluster. This list of clusters make up whats known as a “cluster chain”.

For directories, each cluster contains dirent streams for the directory’s contents. For files, the clusters make up the file’s data.

# Last cluster is marked with this constant value

ClusterLast = 0xFFFF if IsFatX16 else 0xFFFFFFFF

cluster_list = []

cluster_index = FirstCluster

while cluster_index != ClusterLast:

cluster_list.append(cluster_index)

cluster_index = file_allocation_table[cluster_index]

Deleting Files

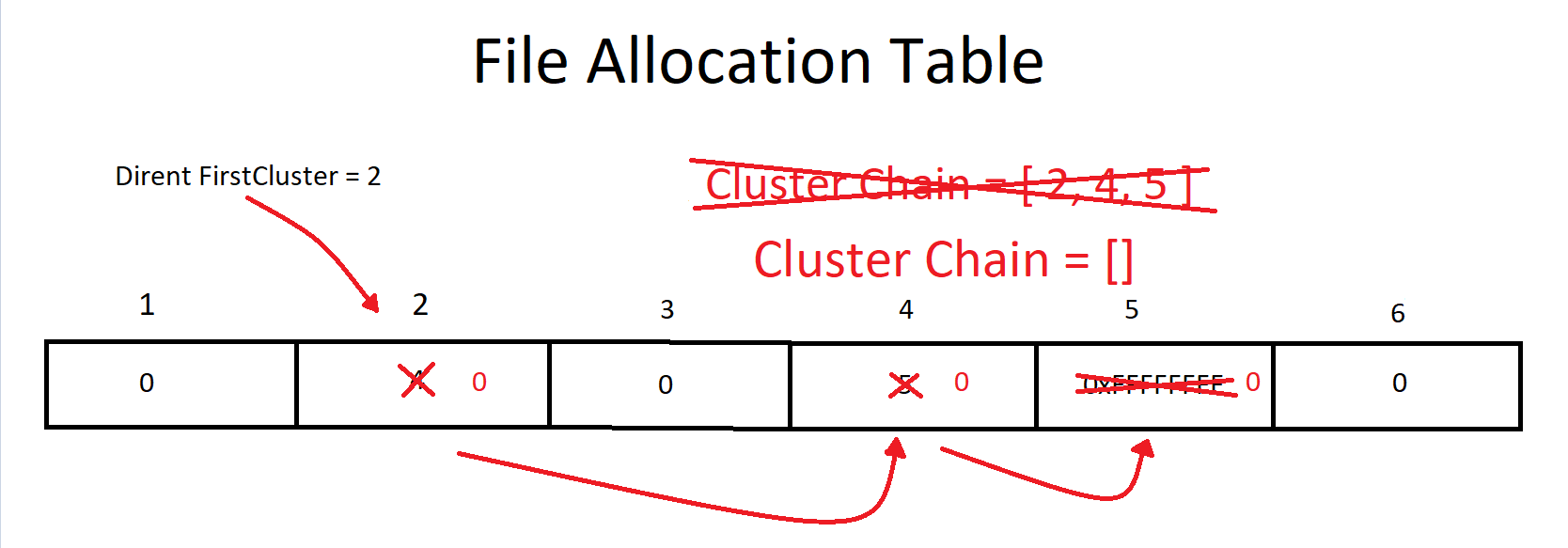

In order to delete files, the Xbox and Xbox 360 kernels zero the cluster chain for the dirent.

ClusterAvailable = 0

ClusterLast = 0xFFFF if IsFatX16 else 0xFFFFFFFF

while cluster_index != ClusterLast:

cluster_tmp = file_allocation_table[cluster_index]

file_allocation_table[cluster_index] = ClusterAvailable

cluster_index = cluster_tmp

# Mark the last cluster as available

file_allocation_table[cluster_tmp] = ClusterAvailable

After zeroing the cluster chain, the dirent’s FileNameLength is set to DIRENT_DELETED.

Fortunately, neither the dirent or the file data is zeroed or entirely overwritten, and that is what makes file recovery possible.

Unfortunately, the deletion process has made data recovery inconvenient for us, as it does not allow us to use the file allocation table on deleted files, forcing us to only extract consecutive clusters instead.

Formatting

For the initialization of a FATX file system, a new FATX header, file allocation table, and root directory is written.

The file allocation table is initalized as all zeroes. The first entry is set to ClusterMedia and the second entry is set to ClusterLast for the root directory.

For the root directory, the first cluster is initialized as all bytes set to DIRENT_NEVER_USED2.

This is one case where important information can be overwritten making data recovery more difficult.

Data Recovery

There are two methods of data recovery implemented in fatx-tools: file carving and metadata recovery.

File Carving

File carving is a simple, but less reliable process. It goes through every certain amount of bytes (amount specified as an option in fatx-tools), and simply checks if the area of bytes matches specific “signatures” for various file formats. If the signature matches, it will then attempt to recover information, such as file name and file size using data contained within that file format alone. This process may only recover consecutive clusters and cannot rely on the FAT.

Extracting information varies per file format. Thus, signatures need to be implemented in code for every file format to be carved. This is currently done for common xbox file formats (xex, xbe, exe, content files), but is a problem when trying to extract game specific files.

Metadata Recovery

Metadata recovery is much more reliable when it comes to file information as it tries to recover file system metadata and then tries to rebuild the file system. It does this by searching for potentially deleted dirents, going through every 0x40 bytes of a specified partition. Using this method, we can quickly and accurately recover most, if not all, file information. This works best when dirents have not been overwritten.

As fatx-tools automatically searches for dirents to recover, it needs to be aware of how to not pick up false positives. To do that, it goes through a series of tests to verify that it is a dirent. If any of these tests fail, then we cannot consider these 0x40 bytes to be a dirent. Here is a list of test cases that each dirent must pass completely in order to qualify as a dirent:

FileNameLengthmust not beDIRENT_NEVER_USEDorDIRENT_NEVER_USED2and if it is notDIRENT_DELETED, then it must be greater than 0 and less thanFileName’s length, 42.FileAttributesmust contain valid attributes.FileNamemust contain valid characters.FirstClustermust index a cluster between 1 andMaxClusters- All timestamps must be valid. The

Yearshould not be from the future and must not be less than the epoch: 1980 for Xbox 360 and 2000 for the Xbox.Monthshould be between 0 and 12,Secondsshould be between 0 and 60, etc, etc.

Throughout the process, every dirent that is found is assigned it’s cluster index. Once it has searched the entire partition, all of the dirents that have been found must then be linked together to form a directory tree.

For every directory that is found, it checks to see if any dirent’s cluster index matches the directory’s FirstCluster index. If it does, then the dirent is added to the directory as a child dirent. Once this process is completed, it will have generated an entire directory tree or trees similar, but not always identical, to the original file system.

Because the cluster chain is erased when a file is deleted, we cannot rely on the FAT to recover fragmented data.

Issues

Neither recovery method is perfect. For example, if a dirent happened to have been overwritten, then the metadata recovery method will not work for that file. In this case our only option is to use file carving instead, to try and find the file directly.

As I mentioned in the file carving section, file carving is still not entirely reliable, at least without some form of user contribution, as unimplemented file formats for undetected files require implementation into fatx-tools to perform recovery. The reason I had initially written the project in Python, was to make it easy for users to write new file carving signatures, but I realized that this may not be very user friendly as it would require users to know Python. Eventually I may create a more user friendly solution for this.

Initially you should start off with metadata recovery. This will try and rebuild the file system using any remnants of file system structures shown above. All the while, it would help to inspect the hdd image by eye in a hex editor to see if there is potentially any data that fatx-tools may have missed. If metadata recovery does not find the files you are hoping to find, you can then try file carving, though this only works for file formats that have been implemented. Your last resort unfortunately would be manual data recovery.

Another issue to note is that both recovery methods recovers file data using consecutive clusters. This is a problem when the file system is fragmented where file data is not stored consecutively.

Conclusion

FATX is a very simple file system and as I dug deeper I learned a lot about other file systems and file system forensics as well. I think this would be a great example to learn from if you happen to have any FATX hdd’s around and/or want to learn about file system forensics.

Fatx-tools are as the name implies, tools. I cannot guarantee that they will recover everything that you hope to find, but I hope to be able to provide a base to work from, as well as provide analysis tools to assist manual recovery.

I welcome any contributions. If you find any issues or have any suggests, please feel free to submit an issue or pull-request in either GitHub repository linked at the beginning of this page.